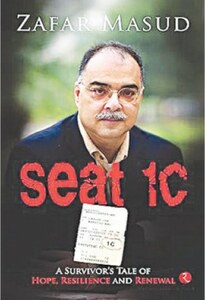

Seat 1C: A Survivor’s Tale of Hope, Resilience and Renewal

By Zafar Masud

Lightstone

ISBN: 978-969-716-305-2

224pp.

Holding a copy of Seat 1C: A Survivor’s Tale of Hope, Resilience and Renewal in my hands gave me goosebumps and flashbacks. It is now five years since I had rushed, along with the rest of the city’s media, to Karachi’s Model Colony, the site of the crash of Pakistan International Airlines (PIA) flight PK 8303, to report on the tragedy. That was the afternoon of May 22, 2020.

The scene looked like doomsday. The air was thick with black smoke from the burning wreckage of the plane, and it stank of burning flesh. The roads were flooded with water from the fire tenders trying to put out the blaze. Some press photographers and cameramen had climbed on to the rooftop of a private school for a better view of the disaster.

The plane had dropped from the sky on top of houses located in a back lane in the middle-class locality adjacent to the airport. A narrow pathway connecting it to another lane that opened on to the main road was being used by the first responders — firefighters, volunteers, paramedics, ambulance drivers. How could anyone have survived this?

The Airbus A320-214 had crashed just a mile short of Runway 25L into the residential area. According to eyewitness accounts, with its engines already on fire, the plane simply exploded into flames upon impact. According to initial reports, all the crew and passengers of the plane had lost their lives, and there were more casualties on the ground, inside the houses.

Most of the residents of the houses, living in such close proximity to the airport, were quite used to hearing the sound of planes taking off and landing, and probably did not realise anything was out of the ordinary until the plane crashed on their heads. Inside the plane, too, there were at least a couple of passengers who, being frequent fliers, remained quite oblivious of any irregularities until it all became very obvious.

Zafar Masud, one of the only two survivors of PIA Flight 8303 that crashed in Karachi five years ago, has penned a first-person account of the tragedy, using a wide-angle lens to reflect on the airline’s decline and the world around him

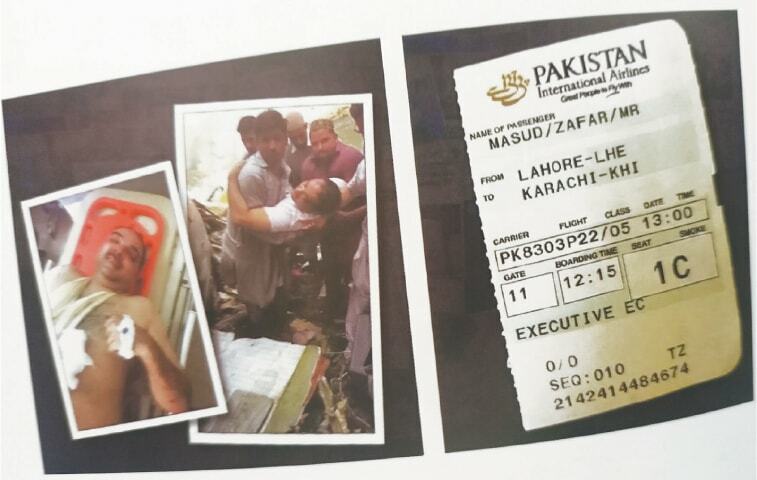

They was 50-year-old Zafar Masud, the CEO of The Bank of Punjab, comfortably strapped in seat 1C up front in business class. And there was 24-year-old mechanical engineer Mohammad Zubair, seated near an emergency exit somewhere in economy. They became the only two people out of 91 passengers and eight crew-members on that ill-fated flight to survive. Masud has now penned this book about his experiences both during and after the flight.

From his position, Masud saw the plane crew crying and praying as they went down. If there were still any doubt about what was imminent, the cockpit door that flung open on descent gave him a clear view of the end. His entire life flashed before him until he fell unconscious.

Masud has pieced together what happened next from accounts from others at the scene, from residents of the locality and from investigators. He was still unconscious and strapped in his seat when it was miraculously thrown out of the plane as it broke apart on impact. The seat was flung on to a third floor rooftop, from where it slid off on to the bonnet of a car on the road.

Knowledge of aviation disasters shows us that passengers seated at the tail end have a better chance of survival in a crash where the nose of a plane hits the ground first. Shaukat Mecklai, one of the two survivors of PIA’s Flight 705 to Cairo in 1965, said that he was seated on the last seat in that plane.

Masud was not assigned seat 1C initially. He was not even supposed to be on Flight 8303 for that matter. Air travel was just resuming following the Covid-19 lockdown. He had booked a morning flight on a private airline before discovering that PIA had a mid-afternoon flight to cater to the Eid rush. To avoid getting up early, he decided to go by PIA. At Lahore airport, having been allotted a window seat, he requested an aisle seat instead, since it would allow him room to stretch his arms and legs.

From his position, Masud saw the plane crew crying and praying as they went down. If there were still any doubt about what was imminent, the cockpit door that flung open on descent gave him a clear view of the end. His entire life flashed before him until he fell unconscious.

Masud also spoke to Zubair, the only other survivor. Zubair actually remained conscious during the entire ordeal, and told Masud that he screamed until the plane came to a halt. His seat belt was still fastened while the two seats next to him were gone. The fire and smoke stung his eyes. He could not see anything but the screams he heard, he said, will stay with him forever. Unbuckling his seat belt he clawed his way towards the only light he could see. It was sunlight from the emergency exit that had opened up. From there he reached the plane’s wing which had somehow been pushed forward due to the impact. From the wing, he jumped on to a house reduced to rubble.

The book isn’t just a tale of survival. The author, who has held various positions of importance and brought meaningful changes to the banking and finance ecosystem of Pakistan, also looks at the alarming institutional decay of PIA. The national flag carrier once played a pivotal role in getting airlines such as Emirates and others across the Middle East, Africa and Asia, get off the ground. Unfortunately, PIA’s Flight 8303 was the sixth plane to crash in Pakistani airspace within a decade.

Masud examines the arrogance of pilots who, like the pilot of his plane, ignore rules while flying, risking the lives of innocent passengers. He listened to the recordings of the the pilot ignoring instructions from air traffic control. He questions why, despite all the incidents of negligence or incompetence by flight crews, ground control and maintenance officials, nothing changes to ensure passenger safety?

There are passages in the book that readers may find insignificant to the story of the crash but Masud has used the wide angle lens to then zero in on real matters. He reflects on many things that have been going on inside his head since the crash. With the resolve of helping society during this second chance on life, Masud is humble enough to know that he is not a chosen one but a privileged one to be allowed to carry on.

Masud had had his spinal cord displaced, broken one of his hands, had multiple fractures and torn ligaments in his legs and had his back burnt. He required multiple surgeries. He began seeing a psychologist while still on his hospital bed to address the possibility of post-traumatic stress disorder. Nevertheless, he was working from his hospital bed just a month after the crash. Eventually, he gathered the courage to travel back to Lahore just four months after the crash, by air on the same route, with the same airline, on the same seat.

Masud has pulled through a long and painful process of recovery, helped by his iron-willed tenacity and drive to continue working and to remain useful to those around him. It is an excruciatingly slow recovery, physical as well as emotional, which continues. This first-hand account is a testament to it.

By Shazia Hasan (@HasanShazia). Published in Dawn, Books & Authors, May 18th, 2025

The reviewer is a member of Dawn’s staff.