If you were in a newsroom in 2020, as I was, the crash of PIA flight PK-8303 in Karachi’s Model Colony on May 22, 2020 will have been seared in your mind. The shocking crash — into a residential neighbourhood a stone’s throw from Jinnah Airport — and the subsequent deaths of 97 people paralysed the country, as did the news that two people miraculously survived the crash.

In his book Seat 1C, one of the survivors — Zafar Masud — explores not only the incident itself but the lessons he has learned in the years since.

Though it does provide a well-rounded account of the crash itself, the book is more in line with the philosophical musings of a man who faced death and miraculously lived to tell the tale. From pondering on the goodness of human beings to contemplating the rot and ruin that characterises most Pakistani institutions, Masud explores a number of themes — and lessons — in the book.

Source: Dawn – Images Facebook

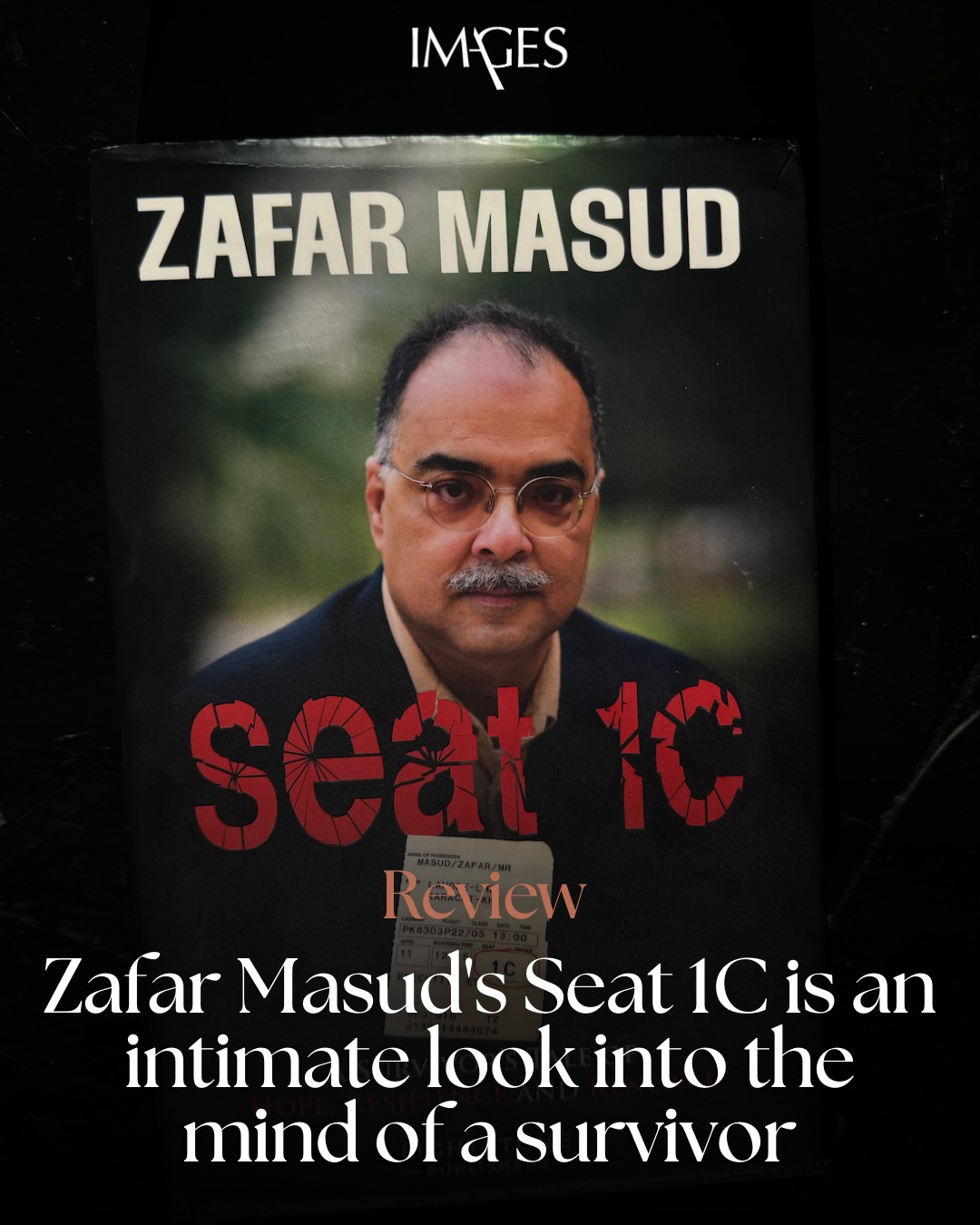

Review: Zafar Masud’s Seat 1C is an intimate look into the mind of a survivor

One of the two survivors of the tragic PK-8303 crash, Masud explores the accident, its aftermath and the lessons he has learned in the years since.

If you were in a newsroom in 2020, as I was, the crash of PIA flight PK-8303 in Karachi’s Model Colony on May 22, 2020 will have been seared in your mind. The shocking crash — into a residential neighbourhood a stone’s throw from Jinnah Airport — and the subsequent deaths of 97 people paralysed the country, as did the news that two people miraculously survived the crash.

In his book Seat 1C, one of the survivors — Zafar Masud — explores not only the incident itself but the lessons he has learned in the years since. One mustn’t turn to Seat 1C for a chronological timeline of events of the crash — it shifts between pieces of information about the crash and its aftermath and Masud’s own musings on life, humanity and everything in between.

Though it does provide a well-rounded account of the crash itself, the book is more in line with the philosophical musings of a man who faced death and miraculously lived to tell the tale. From pondering on the goodness of human beings to contemplating the rot and ruin that characterises most Pakistani institutions, Masud explores a number of themes — and lessons — in the book.

Some of the lessons that stuck out the most were his musings on the willpower needed to get back up again after such a tragedy and the goodness of human beings, illustrated by the three men who rushed to help him after his seat was flung from the plane and landed on a parked car, as well as the outpouring of love he received after being hospitalised from unexpected quarters.

In Seat 1C, named for the seat Masud was lucky enough to switch to last minute that saved his life, we learn about the man as well as the accident. Masud, the CEO of the Bank of Punjab, tells us of his learned family, the morals they instilled within him, his career, his own thoughts after his brush with death and the ever-present question: why me? But Masud isn’t asking why he was in the crash; he ponders instead why he of all people survived the crash.

Unlike the other survivor — Zubair — Masud wasn’t able to climb to freedom or rescue himself. Instead, he relied on the basic goodness of a group of men who pried him from his seat and carried him to an ambulance. He navigates an existential crisis of sorts, wondering why he was saved and why so many others died, eventually making peace with the fact that he did not and may never know why it happened. It just happened and it made him all the more grateful to be alive.

Masud describes himself in the book as more pragmatic than anything else. His pragmatism is illustrated when he says in what he believed to be his final moments, he thought of unsigned insurance papers and how he should have been more outwardly affectionate towards his loved ones. That might be why much of his musings explore historical anecdotes and put into context issues that plagued historical figures as much as they plague us today.

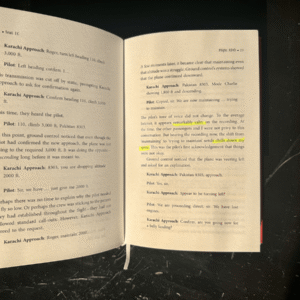

His descriptions of the cabin environment as the plane began to go down, initially unbeknownst to its passengers, were interesting in their utter normalcy. The slight bumps and turbulence, the aborted landing and later the terrifying silence in the cabin as the engines failed.

His story is full of the kindness of others — from a doctor giving him her phone to call his parents at the hospital to the people who rescued him — but it’s also one in which he laments the loss of the Pakistan of yesteryear, where diligence and duty took precedence over cutting corners and personal gain. This is not an uncommon refrain, but in this book, written by a man who suffered the very real effects of institutional rot and cutting corners, it is all the more powerful.

In the chapter titled Arrogance, he explores the arrogance that colours most people’s professional dealings, including, he believes, some pilots who captained planes that later crashed. Had they followed protocol and listened to dissenting voices from junior co-pilots or air traffic controllers, they may have survived, he theorises. He then applies that to other situations, such as the decline of kabbadi in Pakistan, which he linked to the arrogance of older pehlwans who didn’t modernise or regard foreign opponents too highly.

The book itself is an easy read of 200-odd pages and a style of writing that is distinctly conversational. It is as if someone is narrating the story of their life, flitting through memories, bringing up anecdotes from years ago and then coming back to the story for a moment before digressing once more. Despite what it sounds like, this doesn’t make the writing difficult to follow — it just adds a personal touch, as if you are being told a fascinating story.

Seat 1C has been published by Lightstone Publishers and is available at bookstores across Pakistan.